Mobilizing People to Protect and Restore

the Integrity of Rivers and Watersheds

Our Approach AT LIVING RIVERS

For decades, writers, scientists, engineers and environmentalists have documented how economic interests and political alliances overshadowed rational watershed planning in the West. As predicted, our vast plumbing systems of dams and diversions are not only causing significant environmental damage but are also having difficulty meeting increasing demands for water.

Each summer, more and more stories make national headlines: rivers running dry, environmentalists battling farmers, and not enough water to go around. Brokered solutions provide temporary patches, but the disease continues to fester.

the major problem? These systems and the agencies that control them are built on a culture of waste, not conservation. Their missions are not to balance human water needs with preserving the natural integrity of river ecosystems, but to squeeze out as much water as possible to service their customer base.

When agencies do implement conservation strategies, it's to provide water for additional users, not address the inefficiencies upon which the system is built, nor do they address the environmental damage caused by waste. Agencies that might consider leaving water in rivers will do so only if the public water that they receive at a subsidy is purchased back from them by the public at a premium. Remedies seldom gain momentum because they lack the broad popular support necessary to overcome the historic political inertia that has aided in maintaining the status quo. That is, until now.

Since its first public event in March 2000, Living Rivers (formerly Glen Canyon Action Network) has taken the lead in initiating a new approach to watershed advocacy in the West. With a series of restoration initiatives and organizing efforts in both the Colorado and Rio Grande River watersheds, Living Rivers has begun building a popular movement to promote strategies for large-scale river restoration. From the ejidos communities in Mexico, through Indian reservations, farming towns and into metropolitan areas, Living Rivers is engaging people to pressure water agencies to embrace the simple solutions that offer opportunities for restoring our rivers and improving quality of life for millions of people across this arid region.

These effective solutions are readily available but not well-publicized. They involve municipal water conservation, recycling and reuse strategies, increased irrigation efficiency, changes in cropping patterns, and a better understanding of the extensive ecological damage caused by hydroelectric power generation and the conservation and efficiency technologies currently available to replace it.

These solutions are not technically difficult, nor do significant legal obstacles to their implementation exist. These practical, off-the-shelf approaches are economically beneficial and can be implemented immediately. They are, however, politically unpopular with the narrow special interests and institutions that have dominated Western water and power development and planning for more than a century.

The End of Lake Powell Campaign

It's not a matter of if, but when, the Colorado River plumbing system will collapse. Water supply and power generation for metropolitan areas from Los Angeles to Denver will be affected, as will the region's multi-billion-dollar agricultural industry. The sixty million acre-feet of water that can be stored in the basin's reservoirs provide a cushion in times of moderate reductions in river flows, but as is presently being experienced, they are no match for a sustained drought.

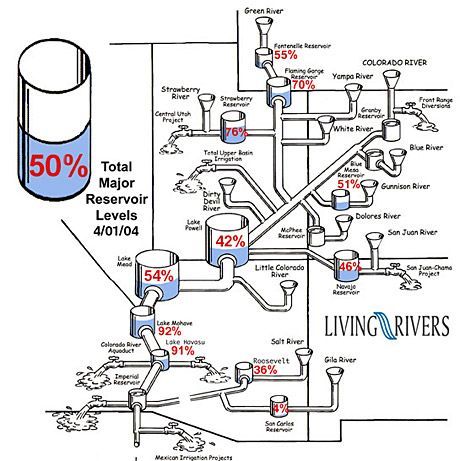

Since 1998, flows in the Colorado River watershed have been well below normal. Historically, Colorado River flows average 13.5 million acre feet per year. Over the past four years, they have averaged only 6.9 million acre feet. Reservoirs are at their lowest level in history and are dropping at a rate of ten percent per year. With below-average precipitation again this year, reservoir levels will continue to decline.

Last year, the US Geological Survey warned that the Colorado Plateau should be prepared for several decades of below-normal river flows and of "severe or catastrophic consequences" should the region experience a repeat of the 1942–1977 drought. Recent flows are, in fact, 15 percent lower than they were when the 1942 drought began.

Despite the likelihood of a major water shortage on the horizon, federal and state water managers continue to keep their heads in the sand.

Living Rivers is working on a two-part program to reform how Colorado River water is managed so that even in years of sustained drought, human needs can be sufficiently met with water left over to maintain flows for critical riparian habitat.

We are demanding that the federal government respond to this crisis and commence a dialogue with the Colorado River basin states of Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, Wyoming, and Mexico to revise the outdated 1922 formula for allocating Colorado River water. Known as the Colorado River Compact, this flawed agreement gives away more water on paper than the river historically delivers.

We are also demanding that the federal government establish water use and efficiency standards for all irrigators that receive water from subsidized federal water projects. Irrigators use roughly 75 percent of Colorado River water, much of it for water-intensive crops such as alfalfa and other feed crops for cattle. Federal programs to facilitate the substitution of vegetables and other crops could save half the water currently being used for irrigation.

Colorado River Basin Map With reservoir levels

Why was Glen Canyon Dam built?

The construction of Glen Canyon Dam was authorized by the Colorado River Storage Project (CRSP), which was passed by a slim Congressional majority on March 1, 1956. Construction of the dam began a year later, with no environmental review of impacts conducted whatsoever. (The National Environmental Policy Act, which requires Environmental Impact Statements to be conducted, was not yet in existence.)

The political motivation for the construction of the dam came from the Upper Basin states (Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, and New Mexico), who wanted to preserve their claims to shares of the river's water as apportioned to them in the 1922 Colorado River Compact. By the 1940s, it was realized that the Compact had grossly overestimated the annual flow of the river; only through impoundment could the Upper Basin states ensure that their claims would remain valid.

The dam became politically feasible, in the eyes of fiscal conservatives, when the Bureau of Reclamation adopted an accounting system called "river basin accounting." Under this system, the electricity generated by Glen Canyon Dam (currently less than 3% of the Southwest's needs) would pay for the construction of other, smaller irrigation dams authorized by the CRSP. In short, Glen Canyon Dam was designed to be a "cash cow" for the Bureau of Reclamation; even today, not a single drop of Lake Powell water is used for commercial irrigation purposes.

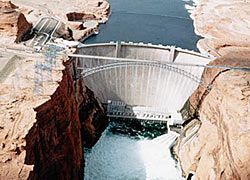

Five million yards of concrete were poured nonstop at the dam site between June 1960 and September 1962; upon completion, the total height of the dam stood at 710 feet. When full, the water in Glen Canyon averages 560 feet in depth, flooding 180 miles up Glen Canyon, making "Lake" Powell the second largest man-made reservoir in the Western Hemisphere.

What Lies Under "Lake" Powell Reservoir?

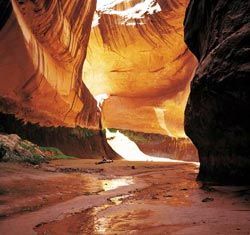

Glen Canyon—the name alone evokes the beauty and tranquility for which the canyon has become famous. Covering a distance of 180 river miles and intersected by dozens of side canyons, Glen Canyon delighted its visitors with the sheer diversity of its wonders, including the Music Temple, Hidden Passage, Cathedral in the Desert, and Tapestry Wall, to name but a few.

John Wesley Powell, the first Anglo to record his journey through the Glen, found in the canyon a sense of respite after his journey through the tumultuous rapids of Cataract Canyon. "We have [here] a curious ensemble of wonderful features," he wrote, "carved walls, royal arches, glens, alcoves, gulches, mounds, and monuments. From which of these features shall we select a name?" He named it, of course, Glen Canyon, to honor the cool groves of gamble oak in which he and his men found shade.

Other writers found in Glen Canyon a beauty that rivaled, or at least complemented, that of the Grand Canyon. Wallace Stegner, winner of both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award, found a sense of comfort in the Glen. "Awe was never Glen Canyon's province," he wrote. "That is for the Grand Canyon. Glen Canyon was a delight."

What did it mean to have such a place drown? For Edward Abbey, drowning the Glen threatened to extinguish the very spirit of the Colorado Plateau. "The Canyonlands did have a heart, a living heart," he wrote, "and that heart was Glen Canyon and the golden, flowing Colorado River."

But Glen Canyon is still there, and it can still be restored. We know from studies of side canyons that were flooded during the big water years of 1983–84 that the canyons are capable of flushing themselves out in a relatively short amount of time. We know that, with proper management, the riparian ecosystems—the willow, the cottonwoods, and the glens of gamble oak—can return. The "bathtub ring" will disappear, and the canyon will recover, just as surely as the Grand Canyon has recovered from the volcanic dams that have twice blocked the river's flow there during the past 5 million years. To say that Glen is gone is to lack imagination. Will it be different? Of course, it will be different. But it can come back.

Historic Opposition to Glen Canyon Dam

The proposal to dam Glen Canyon launched an opposition from its very beginning, in the early 1950's, but this opposition was overshadowed at first by the debate over Echo Park.

When first introduced in Congress, the Colorado River Storage Project legislation contained provisions to build a dam at Echo Park, in Dinosaur National Monument (as well as Glen Canyon, Flaming Gorge, and about ten other sites). It was the proposal to build a dam inside a unit of the National Park System, however, that sparked a national debate. For six years, the Sierra Club, the Wilderness Society, and a coalition of environmental groups from around the nation worked to defeat the Echo Park proposal, and they eventually won. The success of the battle to save Echo Park was galvanizing—historians mark the Echo Park debate as the birth of the modern environmental movement in the United States.

Having achieved victory at Echo Park, however, it soon became clear to many that Glen Canyon, though not a part of the park system, was a place of undeniable beauty, worthy of protection in its own right. Among those who came to this realization was David Brower, then-Executive Director of the Sierra Club, who felt a sense of personal responsibility for Glen's loss.

It should be noted that there was never a "trade" of Echo Park for Glen Canyon. Glen Canyon was always in the CRSP legislation, and the objective of the Sierra Club and its coalition during the CRSP debate was the defeat of the Echo Park proviso, not the legislation itself.

Even in the 1950s, however, there was a movement to save Glen. In 1954, a group of environmentalists in Utah, led by Ken Sleight, formed the Friends of Glen Canyon, whose objective was to revive a near-forgotten 1938 proposal for a national monument that would encompass Glen Canyon and much of the Escalante region. Amidst the clamor of the Echo Park debate, unfortunately, their voice went unheeded.

Yet Lake Powell continued to raise controversy. In 1970, Friends of the Earth and Ken Sleight sued the federal government for allowing the waters of the reservoir to enter nearby Rainbow Bridge National Monument, in violation of the CRSP. The court sided with the environmentalists, but Congress responded by removing the language within the CRSP that had prohibited the intrusion upon Rainbow Bridge.

In 1981, the environmentalist group Earth First! launched itself by unfurling a three-hundred-foot plastic "crack" along the front of Glen Canyon Dam. In 1996, the movement to drain Lake Powell began to gather momentum when the national board of the Sierra Club, under David Bower's urging, adopted the position that Lake Powell should be drained. That summer saw congressional hearings on the proposal, and the Glen Canyon Institute in Flagstaff, Arizona, began work on a Citizen's Environmental Impact Statement to pave the legal way for the restoration of Glen Canyon.

In the winter of 1999, the Glen Canyon Action Network was formed to build the citizen's movement to drain Lake Powell. The reservoir's days became numbered.

How do we address the issue of hydroelectric loss?

The power plant at Glen Canyon Dam currently generates 1,300 MW (megawatts) of electricity when fully operational. This represents enough power for about 350,000 homes, or about three percent of the supply in the six states served by the facility. At the present time, there is a surplus of power on the Colorado Plateau and more power plants going online within the western region; thus, Glen Canyon's power is not needed. Moreover, currently available energy conservation and efficiency programs could easily replace the power lost from a decommissioned Glen Canyon Dam with no cost to the environment. Lastly, the proposal to decommission a large hydroelectric facility for restoration objectives is far from unprecedented. The US Army Corps of Engineers is proposing to decommission four major dams on the Lower Snake River in Washington State that collectively generate 2.5 times Glen Canyon Dam's capacity.

Won't we lose an important water supply?

"Lake" Powell reservoir can store 27 million acre feet of water. That's the equivalent of 27 million football fields (minus the end goals) covered one foot deep in water, or the annual flow of the entire river for two years. Similar to energy supply, there is sufficient storage capacity within the Colorado watershed to meet present and future demand—another 27 million acre feet.

In fact, some water would be gained by draining the reservoir, as an estimated 1.5 million acre feet per year is lost annually due to evaporation from the reservoir and seepage into the surrounding Navajo sandstone. Moreover, an enormous amount of water is wasted through inefficient irrigation. For example, a seven percent reduction in agricultural water use could double the available supply of water for western consumers. Implementing more water-efficient irrigation practices could free up as much as five million acre feet a year, enough to satisfy projected growth needs for some 150 years, about the time the Glen Canyon Dam will have to be decommissioned anyway because of sediment deposition.

What about the sediment?

When Congress approved Glen Canyon Dam, it was clear that sediment accumulation would force the decommissioning of the dam within 200 years of its completion. The reservoir won't entirely fill with sediment for 500–700 years, but because of significant storage capacity losses and potential safety problems that will materialize within the first 200 years, decommissioning will have to occur much sooner.

In working to restore the Glen, the less sediment that accumulates beforehand, the better, which is why advocates are calling for the restoration decision to be taken "now." Although photo documentation and geomorphologic studies have indicated that sediment will be rapidly flushed from the side canyons and the main channel itself, some sediment will have to be removed manually. The sooner this begins, the better. Furthermore, the level of pollution and even radioactive material contained in this sediment will require clean-up at some point, again reinforcing the need to act quickly.

What about Lake Powell's recreation economy?

The most significant contribution to the economy made by Glen Canyon Dam is not water or power, but recreation. "Lake" Powell reservoir attracts 2.5 million people annually. The value of the houseboats alone that utilize the lake is estimated at some $190 million. However, as this was not the primary purpose for building the dam, it should not be the primary purpose for retention. Especially as this form of recreation is having devastating impacts on the local downstream environments. The petroleum products dispensed on "Lake" Powell reservoir alone are equivalent to an Exxon Valdez oil spill every ten years. Fecal matter and other waste deposited in the reservoir are serious public health concerns, forcing periodic beach closures. Of even greater concern is the impact that maintaining the "Lake" Powell reservoir has on the world-renowned Grand Canyon and points beyond. Half the native fish population in the Grand Canyon has been destroyed and declines continue as a result of the cooler water and lack of sediment brought on by the dam. The riparian habitat in the Grand has also changed dramatically, with invasive species taking over the native ecosystem. Moreover, the entire ecosystem of the Colorado River Delta above the Sea of Cortez has been destroyed due to upstream dams, like Glen Canyon, which restrict flows.

This is why draining advocates are promoting a policy of economic transformation through restoration. In the case of Glen Canyon, this has two components. Where once a tourism economy that relied on the reservoir thrived, a new tourism economy that relies on a recovering Glen Canyon will rise. The carrying capacity will unlikely be at the same level as what has been allowed on "Lake" Powell reservoir, but as pollution and sediment problems reveal, the current approach is itself unsustainable. Second, restoration advocates are promoting the establishment of an international restoration research facility to be established in the vicinity of the receding reservoir, of a magnitude comparable to or larger than the national research facilities that were founded after World War II. Combined, such an economic transformation will ensure the economic vitality of the communities surrounding Glen Canyon in a sustainable, river-friendly manner.

Why are people concerned about dam safety?

Rivers are permanent; dams are not. Large dam-building technology is not that much older than nuclear power technology. Large dams have failed in the past and will do so in the future. In 1983, Glen Canyon Dam nearly overtopped and experienced a near-catastrophic failure of its spillway tunnels. This could have resulted in severe flooding downstream, causing the complete draining of the reservoir. The hydrologic conditions that brought this about were far from unique and will occur again. Furthermore, the porous and erosive Navajo sandstone surrounding the dam may, at some point, give way itself. In fact, safety concerns about dams are a nationwide problem; three years ago, the American Society of Civil Engineers gave the US dam inventory a rating of "D" in terms of safety.

How long will it take and what will it cost?

Within a decade of draining the reservoir, it is anticipated that Glen Canyon's magnificence will again begin to manifest itself. In the side canyons, this will occur more quickly, as sediment flushing and plant regeneration occur almost immediately. Within and around the main channel, where extensive sediment deposition has occurred, more human assistance will likely be necessary to facilitate the process. No one expects the Glen to look exactly as it once did; evolution itself ensures this never occurs, but experience gained on smaller river restoration projects has revealed that habitat not only can regenerate itself but often does so much faster than scientists predict.

The actual cost will be more a factor of how much we would like to help the natural process along. The federal government is currently allocating nearly $9 billion to restore a riverine ecosystem critical to the Florida Everglades that was destroyed by development projects built by the Army Corps of Engineers; thus, developing the political support to secure such resources is far from unprecedented.

As for the reservoir's "bathtub ring," rain and other natural forces will erode that back to its original color.

THE Grand Canyon Campaign

Forty years ago, a major public outcry succeeded in stopping the construction of two major dams, which would have inundated Grand Canyon National Park. The famed Colorado River and its unique desert ecosystem would be preserved—or so it was thought.

Unknown to many, a less noticeable but nonetheless lethal blow had already been delivered. The 1963 completion of Glen Canyon Dam, upstream and just outside the park, was beginning to unleash a current of devastation, which now, four decades and numerous violations of federal laws later, has nearly destroyed all the native habitat of Grand Canyon’s famed river corridor.

But it’s not too late to save the Grand Canyon again!

Grand Canyon & Glen Canyon Dam: The Basics

The Canyon

Shaped by the Colorado River over the last six million years, Grand Canyon stretches 277 miles, is a mile deep and is up to 18 miles wide. It was declared a National Park in 1919 and a World Heritage Site in 1979.

Cultural History

Human inhabitants of Grand Canyon have included sophisticated big-game hunters of the Clovis and Folsom cultures 10,000 years ago, Desert Archaic peoples from 6500 BC to 1 AD, and the farming culture of the Basketmaker and Puebloan peoples until about 1275 AD. Today, the Havasupai still live in Grand Canyon; the Navajo and Hualapai Nations have land in the Canyon; and the Canyon contains sacred sites revered by the Hopi and Zuni.

Dams and the Grand Canyon

Hoover Dam flooded the lower 20 percent of the Grand Canyon in 1941. Upstream, 15 miles above Grand Canyon, Glen Canyon Dam stopped the Colorado River's natural flow in 1963. In 1968, public opposition defeated proposals to build Marble and Bridge Canyon dams, which would have inundated much of Grand Canyon between Hoover and Glen Canyon dams.

Sediment and Nutrients

Ninety-five percent of Grand Canyon's sediment and nutrients are trapped behind Glen Canyon Dam. Organic materials mixed into this sediment are used to provide fertilizer for the river ecosystem's health. Instead, the Colorado River in Grand Canyon now runs clear and cold, allowing the green alga cladophora to grow and replace the natural warm-water food web. The absence of replenishing sediment is also causing critical beach and sandbar habitat to disappear and undermining the stability of archaeological sites sacred to the canyon's native peoples.

Truncated Habitat

The isolation of Grand Canyon's river habitat between Hoover Dam downstream and Glen Canyon Dam upstream has inhibited migration and genetic diversity among the native species still found in Grand Canyon.

Water Temperature

Today, water flowing through Glen Canyon Dam is extracted 200 feet below the surface of Lake Powell reservoir, too low for the sun's rays to penetrate. As a result, water entering Grand Canyon is near-constant 47°F. By contrast, before the dam was built, water temperatures ranged from near freezing in the winter to 80°F in the summer. These warm water temperatures were critical to triggering native fish reproduction and maintaining native insect populations.

Flows

Regulated flows currently keep the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon fluctuating daily between 8,000 and 20,000 cubic feet per second (cfs). Before Glen Canyon Dam, flows in Grand Canyon fluctuated seasonally from 3,000 to 90,000 cfs. Spring snow melt brought a rushing torrent of water into the canyon, transporting sediment, building beaches, replenishing the nutrient base on the river's shores and creating vital backwater habitat as the water receded. Low flows were critical for warming water, juvenile fish survival, and maintaining the food base.

Disappearing Species

River otters and muskrats are no longer found in Grand Canyon. Four of the eight native Colorado River fish are gone, and two more are struggling for survival. Native birds, lizards, frogs and many of the canyon's native insects are disappearing as well. In addition, native vegetation along the river's high water zone is absent or stunted due to a lack of nutrients and the invasion of competing non-native plant species.

Designer Ecosystem

The river's altered chemistry, flow and temperature cycles have created an artificial environment, allowing non-native species to dominate Grand Canyon's river corridor. Native plants and animals must now compete with new alien species for habitat and food. These changes run contrary to the mission of the National Park Service, which is to preserve the parks' natural integrity.

Legal Conflicts

Current management of Glen Canyon Dam runs counter to the intent of several federal laws, including the Grand Canyon Protection Act, the Endangered Species Act, the Archaeological and Historic Preservation Act, and the National Park Service Organic Act.

What's Needed

More than $100 million has been invested in failed efforts to reverse the demise of Grand Canyon's river ecosystem. Efforts will continue to fail unless all natural processes are restored: river flow, water temperature, and sediment and nutrient inputs. The simplest solution is to decommission Glen Canyon Dam.

The Restoration Journey

The Slow Road to Failure

1972: In preparation for management plans for an enlarged Grand Canyon National Park, the Park Service begins to research and monitor the degradation of the natural and cultural resources caused by the altered water releases from Glen Canyon Dam.

1982: The federal government launched Glen Canyon Environmental Studies due to heightened concerns about Glen Canyon Dam's impacts on Grand Canyon.

1989: The Bureau of Reclamation initiated an environmental impact study to propose new dam operation methods to mitigate adverse impacts on Grand Canyon.

1992: Congress passes the Grand Canyon Protection Act, requiring the completion of an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) on Glen Canyon Dam's operations.

1996: The Bureau of Reclamation completed the EIS and established the Glen Canyon Dam Adaptive Management Program to guide Grand Canyon recovery efforts.

2004: 200 NGOs demand the Bureau of Reclamation undertake a supplemental EIS on the operations of Glen Canyon due to its impacts on Grand Canyon National Park. Read more...

2005: 130 NGOs support the "One-Dam Solution," a report on the benefits of decommissioning Glen Canyon Dam, as the terms of reference for the Bureau of Reclamation's review of operating Lake Powell and Lake Mead under low water conditions. Read more...

2005: The United States Geological Survey released a ten-year report card on the Adaptive Management Program, which reveals many failings of the AMP Program. Read more...

2006: Living Rivers, the Center for Biological Diversity and other NGOs file suit against the Department of Interior for failing to protect endangered species in the Grand Canyon as prescribed in the 1995 EIS. The lawsuit is settled and a new EIS is planned. Read more...

2007: The Bureau of Reclamation launches a new EIS for a long-term experimental plan for Glen Canyon Dam operations. Read more...

For over 30 years, the public has been demanding that the impacts of Glen Canyon Dam on Grand Canyon National Park be addressed by the Bureau of Reclamation. And throughout this history, the Bureau has failed to encourage any meaningful changes in Glen Canyon Dam operations to reverse the decline of the native riverine ecosystem in Grand Canyon National Park.

The most significant undertaking to date, the now eleven-year-old Adaptive Management Program, was given specific instructions from the 1995 EIS on the steps it should be taken to reverse the ecosystem's decline but continues to ignore most of them.

The program has failed in its principle charge to recover endangered fish. The razorback sucker is no longer found in Grand Canyon, and the humpback chub has declined by 80% to approximately 1,100 fish. Additionally, the dam continues to cause the deterioration of archaeological sites along the river and the rise of non-native species invading the canyon.

This lack of progress resulted in a lawsuit being filed in 2006, the settlement of which brought about the launch of a new EIS in 2007.

Because the evolving focus of this new EIS appears to be the development of recommendations for more studies and not immediate action consistent with what science has already determined, Living Rivers is not confident that this new EIS will generate a productive outcome for Grand Canyon.

This is why it's critical that the public submit comments [LINK 750] on this EIS process and demand that it be focused on mechanisms to restore Grand Canyon first, then on how and if Glen Canyon Dam can be operated so as not to impede this process.

The growing momentum for Grand Canyon restoration has unfortunately prompted Utah Congressional leaders to successfully obtain an annual ban on federal funds for evaluating the best alternative for Grand Canyon's restoration, decommissioning Glen Canyon Dam. Efforts are therefore under way to fully educate Congress on Grand Canyon's fate and the urgent need to support [LINK 610], an unconstrained EIS on the operations of Glen Canyon Dam.

Contemporary Concerns

Experts who have been intimately involved with Grand Canyon restoration efforts are urging more aggressive action.

"It's time to stop pretending that Grand Canyon resources can survive the effects of Glen Canyon Dam. Funding for adaptive management should be used to evaluate how to best decommission the dam while there is still time."

David Haskell, Science Director, Grand Canyon National Park, 1994–1999.

"Adaptive management was not meant to be used as an excuse to avoid making the hard decisions necessary about how, and if, Glen Canyon Dam can continue to be operated in order to restore the native ecosystem in Grand Canyon."

David Wegner, Program Manager, Glen Canyon Environmental Studies, 1982–1996

"Clearly, the adaptive management program has not benefited the aquatic resources in Grand Canyon. The status quo is unacceptable and inaction will doom native fish populations. All alternatives must receive critical and unbiased evaluation—a discharge hydrograph that mimics pre-dam conditions, temperature modification, decommissioning, and other scenarios—all should be on the table."

Dr. Paul Marsh, Zoologist, Arizona State University

"Glen Canyon Dam's Adaptive Management Program has initiated minor flow modifications and limited non-native fish removal, but these mediocre attempts to restore native fish populations and pre-dam habitats are not enough to counter the daily ecosystem destruction imposed by Glen Canyon Dam."

Dr. Joseph Shannon, Aquatic Ecologist, Northern Arizona University

"The price of the creation of Glen Canyon Dam has been the deterioration of the pre-dam environmental attributes of the Grand Canyon. Unless radical measures are taken, this price will remain."

Dr. Jack Schmidt, Geologist, Utah State University

The Battle for New Studies

In April 2004, 200 organizations from across the United States came together to call for a new Environmental Impact Statement on Glen Canyon Dam operations. Federal guidelines warrant preparing another EIS when new information arises that was not considered in the original EIS and could impact future management decisions. Clearly, in the case of Grand Canyon, the continued decline of endangered species raises serious questions about the ongoing implementation of the 1996 EIS' recommendations.

Climate Change: The End of Glen Canyon Dam?

Colorado River flows have historically averaged 13.5 million acre-feet per year. Over the past five years, annual flows have declined to just 6.7 million acre-feet. Federal scientists warn that these lower flows may now be the norm as changing climatic conditions take root in the Colorado River basin.

In most years, nearly every drop of water is diverted from the Colorado River, yet plans are afoot to construct even more diversions. With demand now exceeding supply by 50 percent, a major crisis is looming.

Although ten percent of the country's population is connected to the Colorado River system, water managers continue to ignore this growing imbalance. Changes are urgently needed in how Colorado River water is managed, and it is critical that the environment is not short-changed in the process.

To avoid a major crisis, the federal government must immediately initiate negotiations with the seven Colorado River states to correct the basic flaw of allocating more water on paper than the river has to give. It must then establish efficiency standards and innovative solutions for all Colorado River water users. Lastly, it must conduct a basin-wide environmental impact statement to determine the viability of maintaining the current inventory of dams in light of both declining flows and declining habitat.

If present climatic conditions persist as anticipated, Lake Powell is projected to run dry by 2007, and there may never be enough water to refill it.

Without Lake Powell, surplus water can be stored downstream in the Lake Mead reservoir. In addition, eliminating Lake Powell will make more water available to downstream users by eliminating the tremendous water losses to surface evaporation and seepage from Lake Powell.

The region's energy grid has seamlessly accommodated the 35 percent reductions in Glen Canyon Dam's hydropower generation caused by the changing climatic conditions. Therefore, the public is unlikely to notice any change in energy deliveries from Glen Canyon Dam once output declines to zero.

As Lake Powell's water level decreases, sediment moves more quickly downstream toward the dam. This will accelerate the plugging of the dam's emergency bypass tubes as well as the intake tubes for the dam's generators.

Additionally, even with changes in climate, bursts of high river-flow events could occur via a summer monsoon or a rapid snow melt, flushing decades of sediment buildup within the basin into Lake Powell in a matter of days or weeks.

The lowering of the reservoir is dramatically illustrating how sediment is the major hidden cost associated with Glen Canyon Dam. Climate change or not, there is no technical, feasible mechanism to move sediment through Glen Canyon Dam. Furthermore, the costs of dredging and transporting up to eight tandem-trailer truckloads a minute year-round from Glen Canyon would be astronomical. Grand Canyon needs this sediment, and it would be less costly to remove this sediment from Lake Mead reservoir downstream.

As nature's forces decrease the purported value of Glen Canyon Dam, the viability of a restored Grand Canyon ecosystem increases.

Other Reasons to Decommission Glen Canyon Dam

Glen Canyon Dam was completed in 1963. Promoted as a water supply and hydroelectric facility, Glen Canyon Dam is proving to be an environmental, economic, technical and social liability.

It's Inevitable

The tremendous inflows of sediment into Lake Powell reservoir will soon render Glen Canyon Dam useless. Sediment is fast approaching the level of the bypass tubes used as the first line of defense to prevent floods from overtopping the dam. Once these tubes are blocked, the dam will have to be decommissioned.

Disappearing Water

Lake Powell reservoir loses up to seven percent of Colorado's annual flow through evaporation into the dry desert air and seepage into the porous sandstone surrounding it. Evaporative losses on a single Labor Day weekend could satisfy the needs of 17,000 western homes for a year.

Clean Energy

Glen Canyon Dam has the capacity to provide just three percent of the energy used in the Southwest. The deterioration of Grand Canyon's native river habitat illustrates that this is not clean energy. The power from Glen Canyon Dam could be entirely replaced should ten million homes in the region replace two standard light bulbs with compact fluorescents.

Save Money

Glen Canyon Dam's hydroelectric power revenues are not sufficient to repay the dam's construction costs as required by law. Neither are dam revenues sufficient to finance the rapidly escalating costs of environmental mitigation in the Grand Canyon. More revenue with fewer expenses could be generated by decommissioning the dam and selling the water currently lost to evaporation and seepage from Lake Powell.

Avoid Catastrophe

In 1983, the Colorado River nearly spilled over the top of Glen Canyon Dam and the dam's spillway tunnels nearly collapsed. Described as a once-in-25-year flood event, this scenario is likely to reoccur. Additionally, the highly porous sandstone in which the dam is set is prone to splintering and collapse.

Restore Sacred Sites

Many religious sites were inundated by Lake Powell. One was Rainbow Bridge, the world's largest natural bridge. Despite protests from Navajo medicine people and its designation as a National Monument, it became a victim of the reservoir behind Glen Canyon Dam.

Restore the Joy

A redrock wonderland of nearly 125 side canyons, hidden arches, grottos, and stone chambers is poised to reemerge when Glen Canyon Dam is decommissioned. Nature's forces have repeatedly illustrated that when reservoirs are drained, native ecosystems can return with limited human intervention.

Sustainable Recreation

Recreation on Lake Powell is destined to disappear as sediment fills the reservoir. However, when Glen Canyon is restored, hiking, rafting and biking will quickly take their place, generating significant income as they do elsewhere on the Colorado Plateau.

Species in Peril

Extirpated, endangered, and sensitive species along the Colorado River in Grand Canyon National Park

X=Extirpated-regionally extinct

E=Endangered

Candidate for listing as threatened or endangered

SC= species of concern.

FISH

Colorado pikeminnow (X)

Razorback sucker (X) Bonytail Chub (X)

Roundtail chub (X)

Humpback chub (E)

Flannelmouth sucker (SC)

Bluehead sucker (SC)

Speckled dace (SC)

AMPHIBIANS

Relict leopard frog (C)

Northern leopard frog (C)

REPTILES

Zebra-tailed lizard (SC)

Desert-banded gecko (SC)

BIRDS

Yuma clapper rail (E)

Southwestern willow flycatcher (E)

Yellow-billed cuckoo (C)

MAMMALS

Southwest river otter (X)

Muskrat (X)

Long-legged myotis bat (SC)

Western red bat (SC)

Spotted bat (SC)

Pale Townsend's big-eared bat (SC)

Allen's big-eared bat (SC)

Greater Western mastiff bat (SC)

INVERTEBRATES

Pre-dam insect assemblage

Kanab Ambersnail (E)

PLANTS

Old high water zone assemblage

Studies show that many of these species are seriously impacted by the presence of the dam. However, a lack of pre-dam population data on some species makes it necessary to base judgments solely on current knowledge of habitat requirements.

DONATE AND make a Difference

You can support our river restoration projects by donating conveniently through the PayPal button below, sending a check via mail, or giving thorough estate planning options. Our federal identification number is 87-0668658. If you are directing your donation to one of our fiscally sponsored projects, please make the check payable to Living Rivers and specify the project's name in the memo line. Your generosity ensures the continuation of vital conservation efforts along the Colorado River and its ecosystems. Thank you!